May 1, 2017

By Jake Precht:

Chemistry Ph.D. student Sarah Vorpahl will bring her passion for clean energy and policy to Washington, D.C. this September as a 2017-2018 Materials Research Society (MRS) and The Optical Society (OSA) Congressional Science and Engineering Fellow.

Her colleague in Clean Energy Institute (CEI) Chief Scientist David Ginger’s lab, Jake Precht, interviewed Sarah about her research, her experience as a CEI Graduate Fellow, and what’s next in her career.

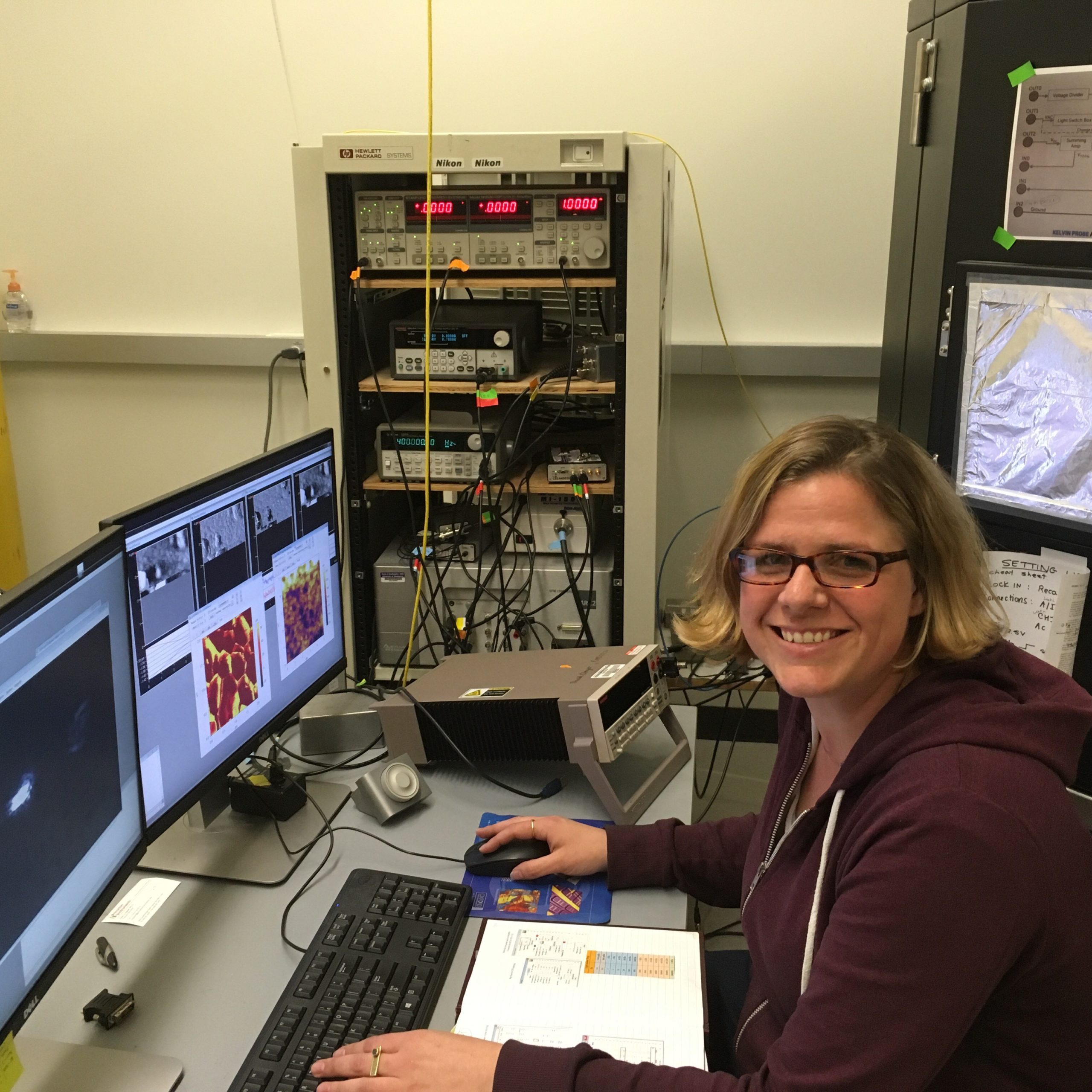

Jake Precht (JP): Tell me about your work investigating next-generation solar cells with CEI Chief Scientist David Ginger.

Sarah Vorpahl (SV): My research in the Ginger Lab is broadly on a class of new solar cell materials that can be made into solution processible thin-films. This means that the solar cell absorber material is available as an ink that can be rolled out much the same way a newspaper is, via a roll-to-roll processor. Making solar cell materials in this way allows for a lot less material to be used, which both decreases the cost and increases the flexibility.

My most recent work focuses on an exciting new material called perovskite, which has gained attention for its swift rise in device efficiency within a relatively short period. Despite the impressive gains of these materials in the past 5 years, there are still many fundamental questions that remain open about perovskites. Our lab is interested in probing the fundamental electronic and material properties that underpin issues of device stability and other defects. I am particularly interested in understanding how the electromechanical properties of these materials, such as ferroelectric domain orientation, relate to their device performance as solar cells. I use atomic force microscopes to investigate these fundamental properties by creating maps with nanoscale spatial resolution that can then be correlated and compared with the overall performance at a bulk scale. Being able to ask fundamental questions about the local nanoscale properties under relevant operating conditions allows for a more dynamic understanding of how perovskites function as a solar cell.

JP: How has CEI helped you in these studies?

SV: CEI has been a critical component to my graduate research. I have benefitted from the combination of having both world-class instrumentation as well as a vibrant community of graduate students and faculty in clean energy materials at my fingertips. I also think that because of CEI, UW has been able to attract top-notch postdocs and new faculty, which has had a direct impact to my lab. I have taken advantage of the CEI Graduate Fellowship and academic meetings (such as the Orcas Conference) that have allowed me to interface with people about research related to my field.

JP: How has CEI has helped you achieve your career goals?

SV: CEI has provided me with incredible opportunities to interface with policy makers, industry, and entrepreneurs in the WA state cleantech ecosystem. Since CEI is a member of the CleanTech Alliance, I have been able to take advantage of their events such as the CleanTech Breakfasts featuring important figures in the cleantech community as well as other networking events. Because I have made my interest in policy known within CEI, both my PI David Ginger and CEI Director Daniel Schwartz have given me amazing opportunities to represent CEI and discuss clean energy with local policy makers. For example, last October I served as a volunteer note taker at a Utilities and Transportation Commission workshop on innovation and the role of regulation. At this meeting, I learned about the challenges and unintended consequences of policy that seeks to satisfy the often-clashing interests between innovators, utilities, and regulators. CEI has been a hugely important institution during my graduate school career and has absolutely allowed me the space to grow and shape my policy understandings and beliefs.

JP: What other organizations are you involved in at the University of Washington (UW)?

SV: Four years ago, I founded Women in Chemical Sciences (WCS) to create a culture of inclusion in the UW Chemistry Department and beyond. Under my guidance as president, WCS became a fully funded group in the Chemistry Department, held dozens of workshops and career talks, and brought in world-famous speakers through competitive grants from within the university. I was also one of the founding members of Diversity in Clean Energy (DICE), a group within CEI that helps bring in diverse voices from the clean energy community. Last year, citing the need for further conversations across campus about diversity in STEM, I worked with CEI Graduate Fellow Nicholas Montoni to hold a one-day seminar called, “Strengthening STEM through Diversity.” The event brought together over a hundred students, faculty, and staff from across campus to help amplify the experience of minoritized students on campus.

I have also been fortunate to spend some time working with other policy students on campus. Realizing my desire to translate my work to policy, I dedicated a year to advanced coursework in this field through the Evans School of Public Policy at UW and earned a Ph.D. Concentration in Public Policy and Management. I pursued this extracurricular research to understand the fundamental way to ask questions in this field and I have been able to apply these ideas directly in the arena of energy policy.

JP: Why do you think it’s important to increase women’s and other minority group’s participation in STEM?

SV: Bringing a diverse voice to science makes it better. Not everyone is given equal access to the educational, emotional, or community resources necessary to achieve in STEM from an early age and especially later in college and beyond. Increasing representation and access to STEM means both increasing our early education in these subjects as well as having a faculty and student body that more closely mirror the demographics of this country. A major part of understanding the issues of diversity in STEM is talking about it! So creating safe places to share experiences, especially from those that have been successful, is critical to shining a light on the ways that minoritized students experience hardships as they go through their science careers.

JP: I know that you’re active in science policy advocacy here in Seattle. Tell me about your work for the Washington State Department of Commerce.

SV: After the election, feeling a little dismayed and helpless, I contacted Brian Young, the Governor’s clean technology sector lead at the Washington State Department of Commerce, whom I had met at a CleanTech Alliance event. I asked if I could intern at the Commerce Department to see how a technical person might have an impact on policy. I ended up working with the energy department on writing about the success stories from the Clean Energy Fund (CEF). CEF is an innovative program in Washington state that sets aside money from the capital budget for the development, testing, and deployment of new clean energy innovations to help reduce carbon emissions and increase the security and flexibility of the grid. I have been able to interface with all aspects of the clean energy world in Commerce, including the folks doing the daily policy work for clean energy in the state government, the big picture thinkers, the business development folks, as well the engineers who are working to make sure we can successfully transition to a new, shared energy economy. Seeing each of these roles has given me the opportunity to see how unique our energy landscape really is.

JP: As long as we’re talking science policy, now’s a great time to say congratulations on your recent Congressional Fellowship! What are you going to be doing in Washington, D.C.?

SV: I am honored to have this chance to work in D.C. I will be working in a congressional office staffing either a senator or representative on science-related issues. I am in a cohort of about 20 other fellows who will also be working on science issues. I hope to focus mainly on energy policy, but I am sure that I will have exposure to many different subjects as part of my work! I also get to take the same civics crash course as all freshmen congressional representatives. Hopefully I’ll learn a little more about how a bill becomes a law than what I know from “Schoolhouse Rock!”

JP: What is hindering widespread clean energy implementation in the United States?

Sarah Vorpahl in front of the White House

SV: I think the good news is that there are great advancements in technology on the way, especially at the academic research level! For example, we are seeing real potential in materials like perovskites for solar. Additionally, scientists are continuing to improve large-scale storage to help mitigate these distributed energy sources on the grid. I think that the biggest hurdle is an institutional one. Utilities in general are a very arcane business model and the institutions that regulate them create bureaucratic lag. Additionally, we have the very real hardware problem that comes with our aging and outdated electric grid. I believe that there are many progressive utilities that want to provide greater and cleaner options for energy consumers, but they also need to make money at the end of the day. Figuring out how to work with utilities and help mitigate cost and risk for modernizing the grid and bringing more distributed energy online is one of the greatest challenges moving forward for clean energy.

I think that policy can step in to both incentivize renewable energy implementation as well as mitigate some of the risk involved with being an early adapter. Innovative policy like the clean energy fund here in Washington state, and what’s happening in New York, helps mitigate the risk to utilities and other institutions for being early adopters of clean technology.

JP: Thanks, Sarah! Good luck wrapping up your Ph.D. and starting your fellowship in D.C.!

Jake Precht is a second-year graduate student in CEI Chief Scientist David Ginger’s lab.